#24 TOWARD A POETICS OF TRANSLATING THE DOHA–Part One: The Rut of Suchness Flows

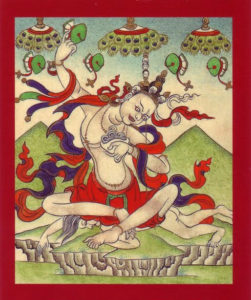

Krishnacharya riding his zombie

In the Indian tradition of Buddhist poetry, as inherited and practiced by the Tibetans, we get a predominant didacticism–it’s poetry that’s meant to explain the dharma to you. But that’s not everyone. The Indian siddhas (Sanskrit: “realized ones,” “accomplished ones”) aren’t so academic sounding, though they may be teaching dharma; when they speak , it’s more like throwing thunderbolts.

Without translators, there would be no classical Buddhist poetry at all for most of us. They’ve got to bring it into something other than Tibetan, Sanskrit, Apabrahmsha, Pali, or whatever it is, if we’re going to read it, and so you have to expect that they’re getting the meaning right because, after all, if they don’t, then the wrong wording distorts the teaching.

The only problem with this is that it’s still poetry, and there’s a reason it got put into poetry to begin with, one that’s not replicable with prosaic translations. If Krishnacharya (Indian, located somewhere in 800-1000 C.E.) wanted to put it in paragraphs, that’s what he would have done. Krishnacharya, famed for riding around on the back of a zombie with hand drums and umbrellas rotating in the sky above his head, did exactly as he pleased, you’ve got to think.

I’ve done translations of poems from French, Spanish, Korean, Japanese, Chinese, and Tibetan. Don’t be too impressed–it’s not like I know all these languages. I’ve found the English equivalents or worked with native speakers, and worked as well from other translations. That’s cheating, isn’t it? Yes, in a way, it is, but as my lineage is poetic not scholarly, my interest remains finding the living wording. Here I follow New York poet Ted Berrigan who saw the line as the basic unit in a poem. Great lines=great poems. If each line lands with impact and resonance, you’ve entered the poem’s playground, endowed with many surprises.

So I admit it; I have an attitude. Scholars have them, too–scholarly attitudes of right and wrong in translation, for instance, but when it comes to translating poetry, there’s no perfect exactitude. Unavoidably built into translation itself, one language expresses itself one way, and the other another. You can say “red” or say “rouge” and seemingly mean the same thing, but in two languages with a common root, English and French, the sound of the English word stretches the vowel but stops it suddenly with the “d.” There’s a certain intensity this invokes. The far more sensual French word, with its long drawn out vowel and gently extending soft “g” sound, brings you more immediately to its erotic implication.

So, the point is, if there are automatic connotative differences in the sounds of two closely related words, what can you expect from the sounds and poetic effects that come from two highly distinctive languages originated on opposite sides of the planet? Add to this cultural assumptions and connotation–both long-term and within current usage– the syntactical structure, how their poetic meters work, and more, then two words with the same meaning get pushed potentially quite far apart.

I used to attend an ex-pat sponsored open poetry reading in a bar in the Hongdae neighborhood of Seoul, South Korea, a university area that fostered a music scene and other arts. During some kind of international poetry event, the reading moved to Olympic Park, to stadium seating overlooking a stage against a Han River backdrop. Some people from maybe the Spanish or Mexican embassy came out and recited Spanish language poems. The contrast presented my daily ear by the soft, curving, warm edges of Spanish landed me instantly and vividly in a completely different world. Monosyllabic Korean, where all the spoken emphasis elongates at the end of a sentence or clause, felt startlingly different, a different consciousness altogether. You could feel the physical bodies behind each–their gestures, comportment–alive in the words.

Therefore, if you’re going to put Pablo Neruda in Korean and Ko Un into Spanish, you will not easily attain the same feeling or maybe the same meaning. But when it comes to dharma, isn’t the meaning paramount?

Well, yes, but what gets ignored here is that the sound of the poem is part of the meaning, part of why it lands for the reader. You want the poem to find the target, to be felt, to become an experience for the reader. The translator can’t merely concern him/herself (and LGBTQetc.) with meaning if the sound functions as a determinative part of the meaning. That’s why it’s an art, after all. Take these two famous lines from English poet John Keats (1795-1821), describing a cup of wine:

…With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,

And purple stainèd mouth…

The shape of the words invoke the experience of those bubbles, a finely observed but tangible, textural sensory detail. You can’t just be literal about it, if you’re translating it. You can’t say, “There are bubbles on the edge of the cup, / he’s got purple stains on his mouth.” The metric effect disappears. No one will remember that as great poetic expression. It won’t have full impact, despite its literalness.

Lacking fluency in any of these languages–beyond some feeling for the Latinate kind–I’m not going to be much help with this. But what I do retain is a sense of whether the poem succeeds as a poem in English, and since we’re reading them on the page in books, here I would insist that translators find a way to make these tantric poems into something that lives as a poem. Then the impact of the dharma in its lines will have a firm yet nimble footing.

The doha, an essential poetic form of India favored by the Buddhist siddhas has become known to us through the Tibetans as “a song of spontaneous realization.” In other words, the yogi improvises a song on the spot for an immediate situation and whomever constitutes its audience. It declares the yogi’s realization, in whatever way it comes out at that moment. For instance, Saraha (circa 8th century), confronted by the local king in front of the citizenry over his outrageous and questionable behavior, addresses his circumstance with confidence and concision (these are all my versions of the originals):

If I’m like a swine clinging to samsaric mire,

Point out to me the stain in a pristine mind.

If nothing can pollute it,

To what can it be bound?

Saraha is saying that if you think I’m a pig wallowing in worldliness, show me what’s obscured about my unconditionally pure mind free from dualistic clinging. This kind of high end, tantric sass comes with the territory of the doha, at least as the siddhas composed it.

Less understood, in India the doha had a structure of metered, rhymed couplets sung to a melody–the Charyagiti (Sanskrit: “Songs of Yogic Conduct”), for example, collects yogic dohas originally employing the melodies of various ragas. The Tibetans seemed to have abandoned or de-emphasized the technical sense of the doha for its crucial inspiration: to articulate the embodied truth of realization on the tongue.

Trying to be faithful to the wording and still get the lines to rhyme in another language comprises an enormous headache for the translator, and easily yields ridiculous circumlocutions to make the poem stay true to the meaning and still rhyme. While you might sometimes get it to work, that won’t get you consistently to effective poetry, just a lot of awkward or plain, bland phrasing.

The same follows with meter as the meter’s formulated to Sanskrit patterns, not English ones. Modern English language poetry has largely, though not entirely, shifted away from metric patterns to spoken rhythms, but here’s where the translator might be aided in poetic effect. The siddhas don’t lack for personality, as expressed in their poems, and they amalgamate the erotic and esoteric with a free sense of liberated impunity and sometimes surreal tantric paradox. Krishnacharya (referring to himself here as “Kanha”):

Kanha gets drunk & playfully enters

The lotus-bed of co-emergence, growing tranquil.

Just as the bull elephant mates with the cow,

The rut of suchness flows.

Not a high falutin’ monk nor holier than thou saint, he gets drunk like the hoi polloi. But, pulling the rug, he’s drunk with co-emergence, bliss engendered through experiencing the unity of samsara and nirvana. The lotus, a classical Buddhist symbol of purity, becomes a bed of many where he frolics sexually, leaving him at peace. The softer sexual tone alters aggressively with the metaphor of the bull elephant in congress, as some epic, primal intimacy with power, by which “the rut of suchness flows.” “Suchness” (tathata), the innate nature of all phenomenal reality, the pervasive ordinary mind, gets identified with the unstoppably lustful and abundantly, unavoidably physical. He goes on to proclaim:

I’ve stolen the jewel of ten powers that pervades the ten directions,

And tamed the elephant of ignorance with ease.

The kind of guy you’re dealing with here screws on a bed of lotuses, mates like a bull elephant in rut, steals the jewel of power, triumphs over everywhere, and simply takes the elephant of the whole existential problem by the nose and leads it like a pet. (This is what hip-hop would be like, if fueled by sacred outlook and tantric paradox: “I got 99 problems, but they all co-emerge!”) This attitude isn’t a scholar’s, but definitely is a poet’s. Make his proclamation sing in English, occupy that irascible, insouciant voice, and you’ve captured something of the sound that gives the meaning impact. Then maybe the expression of the dharma strikes the receiver of it right where the mind stops…and that’s how poetry works.

Krishnacharya, beneath his umbrellas and hand drums

Krishnacharya came to town

Riding on a zombie…

….with two six guns

and umbrellas and hand drums in the air….

Outstanding work here— poetry and dharma both working in the realm of “stopping mind” are quite the pair, and i do think that you are in a prime position to have them tango for us on the page. I for one vote for more of this subject matter—OK, I know you often aim for your subject matter to be perceived via a dharmic playground…but just sayin’…the subject of poetry and dharmic practice is one you are very intimate with, so I hope you will exhaust your deep well of this in future posts. Leave nothing behind! (we can’t read an unwritten blog, or your mind for that matter, so do it soon, and on-goingly ;).

Old sacred texts tell us if someone asks for a “teaching”, even if it is one person, the teacher is obliged to do it. Haha. Tag. Your it. (And i think they have to be sincere. And I am…)

The next post will continue on this topic, and there will be a third one as well. Anything I’m writing on here tends to be what obsesses me on a daily basis, so there’s bound to be more!