#26 TOWARD A POETICS OF TRANSLATING THE DOHA: Part Two—I Have the Key to Enter the Vision

Come converse with the dakinis

The dakinis (Sanskrit: “sky-goers”; goddesses who appear in many forms) confront the Indian tantric master Tilopa (988-1069), challenging Tilopa with their own tantric doha:

The born-blind looks at, but he cannot see the forms;

A deaf man listens to, but he cannot hear the sounds;

An idiot speaks, but he cannot understand the meaning.

At least, that’s how Fabrizio Torricelli and Sangye Naga translate this from Tibetan to English (The Life of the Mahasiddha Tilopa, 1995). I don’t mean to pick on them here, exactly. They did us a favor by translating Marpa’s account of Tilopa’s life. Tilopa originated the Kagyu lineage, still going to this day. Coming as a third generation lineage figure, once removed from Tilopa, Marpa likely wrote the earliest available biography describing Tilopa’s life and spiritual path. Nevertheless, it’s too prolix for poetry, if you ask me. Here’s my version:

The blind look, but don’t see;

The deaf listen, but don’t hear;

Idiots speak, understanding nothing.

The dakinis are challenging (and insulting) Tilopa. He’s come into their abode where he seemingly doesn’t belong, and they’re implying that he’s blind, deaf, and stupid. They’re making a vigorous, confrontive, as well as enigmatic statement here.

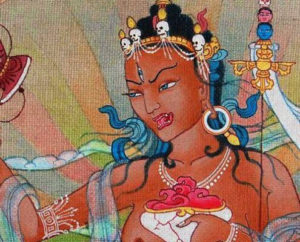

Does this dakini seem like she minces her words?

Good poetry always relies on concision, whether it has long or short lines. Words aren’t wasted; that’s fundamental to achieving poetic effect. Torricelli and Naga’s version has eleven words in the first two lines, and nine in the third. The lines in Tibetan are each seven syllables (not words) long. If you count their English translation syllables, it’s 12-13-14. I’m counting them, but I don’t imagine they did.

Trust me when I say I’m sympathetic to the problem of getting the original over into English in about the same lengths. That can be completely impossible if the original language has a one syllable word and the English equivalent has three. If you then need a preposition for it to make sense, you add one or two syllables more.

Is this interesting to the casual reader? Why am I going on about this? Because now you’re looking under the hood of the poem, as to how it gets constructed. But I’ll trust here that you can immediately feel the difference between the first version and mine. By simply getting to the point without all the extra clutter, there’s impact: “Idiots speak, understanding nothing.” That has some emotional force through brevity and rhythm (a spoken word rhythm here) that simply leaks out of the extra wording: “An idiot speaks, but he cannot understand the meaning.” Now it’s explaining it to you; its effect doesn’t feel so much like dakini proclamation—and dakinis definitely don’t tend toward ponderous didacticism.

Translators feel a demand to get every bit of the wording translated, though you can step on the message this way. That’s my point. Some choose to be as literal as possible, which works great when it works great, but lacking the same connotations in English, it can easily not come across.

I find this to be a special problem when it comes to translating important vocabulary, that in Tibetan also has Sanskrit antecedents, but may have nothing like it in English.

The informed Buddhists out there, what do you think this translates: “sheer essence dimension”? How about “noetic being”? Or: “primordial contact with the total field of events and meaning”? That ought to explain it, doesn’t it? Or this one– “reality dimension”? How about (and maybe this gives the game away)–“the Buddha-body of Reality”?

Translators want to explain it to you. After all, if you leave it in the original language, you’re not translating it, are you? Nevertheless, they’re attempting this word (in Sanskrit): dharmakaya. “Dharma” here means “truth” or “reality,” and “kaya” means “body” or “embodiment.” What’s the body of truth or reality, or what’s its embodiment? The Buddha’s enlightened mind. That’s the term we’re using. In Tibetan, chos sku, a literal translation by the Tibetans as “dharma” (chos) and “body” (sku) though maybe there’s some sense here of “exalted embodiment” or something like that.

I’ve tried to accept that if the tradition can come into English, it needs English terms like all the Sanskrit has Tibetan equivalents. But after mucking through “sheer essence dimension” in this book, “reality dimension” in that book, and “primordial contact with the total field of events and meaning” in the one after that, I’m exhausted. I have to relearn the damn word every single time. Trungpa Rinpoche used the Sanskrit “dharmakaya.” I only had to learn that once, not eight different times in eight different books. No matter how you fashion it, what you’re translating is dharmakaya, and half the term, “dharma,” is already in English. In a poetic line, you have to use short-hand a lot of the time, in any case, or how is it going to fit?

It needs to fit because you’re respecting the form of the poetic language. Each line should produce resonance, such that the reader or hearer feels something more. How something communicates depends on the form it takes, as I mentioned in Part One.

Consider again Torricelli and Naga’s rendering of Tilopa explaining himself to the dakinis:

A mind where there is no mental elaboration,

Where even a particle of dust of recollection (smriti) will not arise,

This is the being as such of thinking, the Dharmakaya of the being of phenomena (dharmata).

I have the key to enter the vision.

They’re not doing terribly until they hit the third line. Remember the 7 syllables? That’s still how the Tibetan reads, but now they’ve got to spell it out to you somehow, or they think they do. But let me deal with the first two lines:

A mind without elaboration,

Where not even a dust mote of recollection arises…

While the parenthetical insertion of the Sanskrit clarifies things—if you know the Sanskrit–it clutters the lines of course (this is also something you can put into endnotes rather than sagging the lines with it). You can argue that there’s a verb in the first line, but I didn’t put one in. Why not? For concision, I made the line a dependent clause. Hear the to-the-point quality: “A mind without elaboration.” You get the meaning, don’t you, despite sacrificing the original syntax?

What about the next line? It’s pretty close to the original words, it has the same meaning, but why not use “mote” (one syllable) instead of “particle” (3 syllables)? Also their line strings itself out by going ____ of____of____. Good grief, get to it! Don’t string us along!

But that’s still not as bad as the third line that barely makes its point with 24 syllables! It makes my bardic skin crawl! Does it even make its point, after all of that? It’s hard to make out. In fairness, this isn’t a terribly obvious thing to translate, but let me take a crack at it:

Is the mind itself, the suchness of dharmakaya.

As far as I can tell, Tilopa’s telling us that what we think of as the mind is actually “suchness,” the essential space before the concept of self and other arises, and this is the ultimate identity of enlightenment, the “dharmakaya.” As poetry, it’s an abstract line void of image, but on the bright side, this version leans on its strong vowel sounds, does its job of pointing out the nature of mind to both the dakinis and to us, and gets in at 13 syllables, almost double the original Tibetan, but less than half the length of Toricelli and Naga. With the last line feeling relatively solid, I’ll leave their version of it:

A mind without elaboration,

Where not even a dust mote of recollection arises,

Is the mind itself, the suchness of dharmakaya.

I have the key to enter the vision.

The dakinis want to know what right Tilopa has to come into their mandala and inner sanctum. What authenticity allows him to be there? He declaims his right by pointing directly to the nature of awakened mind, what it actually is. What is it? It’s without conceptual elaboration, without so much as a mote of trying to recollect contemplative thought or even meditation. It’s not the divisive, conceptual mind; it’s the mind’s own innate suchness, its ultimate truth as primordial contact with the total field of events and meaning, er, I mean, its true enlightened nature called the dharmakaya. With this understanding as his key, he can open the door into their celestial abode, into its pure vision.

It’s a dramatic and profound moment. Translators need to take such things seriously or they step on the message. And after all, isn’t the most important thing that we get the message?

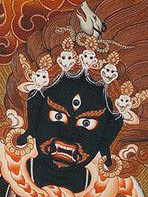

Tilopa–finding words for dharmakaya

(Coming up: TOWARDS A POETICS OF TRANSLATING THE DOHA: Part Three–Jackals & Vultures Weep!)

Hey Gary,

I totally agree with you and appreciate your translation. Though there is a place where more words rather than less in poetry can serve, translation of the Dharma is not one such. I struggle a lot with what I consider to be poor translations, and myself look for the essence over the literal word-for-word approach, which as you say, steps on the message. I have this conversation with many friends and fellow students.

What I would add is that for me I struggle even with “Dharmakaya.” I constantly have to translate the kayas, to look them up, over and over again. For this reason, I prefer “truth body.” To me, as a Westerner and a poet, that leaves space for what we are getting at, without making it sort of hopelessly exotic and external to myself.

Thanks for engaging my mind in ways that are meaningful to me,

Maxime

I think there’s no good way around the “dharmakaya problem” (Is dharmakaya a problem?). When someone does translate it as “truth body,” I’m usually glad because I can at least identify what it is. What is it? Dharmakaya. But sure, that is the reason for translating these words into English, except we still have to learn what they mean, despite the translation.

Very nice, and fun to read!

I am starting to feel like I should do some translating versus write my own Buddhist inspired poems- that way i could use the word “suchness” without it immediately being struck down by my trusted editors. And believe me I’ve tried, as i think it does exactly what it sounds like it is doing- one cannot put their mind on it- it pervades boundaries. BUT i end up having to come up with an image, which will take a lot more words, which if it works, will dance a jig in the body or take your head off like a good poem should.

I do agree likewise about the word Dharmakaya. So tempting to use, but not kosher when writing a poem “for non-Buddhists” – in quotes bec i don’t usually write poems with any kind of audience in mind until i am on the far end of the revisions and see i need to be clearer, more “concise”! And then, I do like the idea of spreading the seeds of dharma this way, too…

This could merit a very long reply, to the point I’m thinking I may have to write another series of blog posts on writing Buddhist poetry in the modern, western world. As you may not know, in the Buddhist category of the ten fields of knowledge, poetry is on the list. It’s No.1, considered the least important, but Buddhists still thought it important enough to make it essential to your education, as modern western educators manifestly do not.

Can you put an abstract Buddhist term like “dharmakaya” into a western style literary poem? Why the fuck not? You can do anything you want!–that’s the beauty of it. Ezra Pound put in Chinese characters, and it’s safe to say that the average reader didn’t know what they meant. But in any case, you’re free. Take the freedom, would be my advice. You can always explain it in end notes, if that seems important.

Ezra Pound used to frustrate me because he expects that the reader will somehow make sense of all the references to his personal reading. I definitely don’t see a point in that, but then again, you can understand that he’s just taking his materials and shaping his poem in a way that pleases him. Whether you can read French or Greek in the Greek alphabet or know who Phillipus Cappello was, well, that didn’t keep him up nights. He wanted to use everything at his disposal and transformed it freely. There’s your tradition of western modernism.

If you’re afraid that people won’t understand it, they may not anyway, even without a single foreign abstraction in your lines. The vajrayana tradition’s sense of writing poetry had no problem with Buddhist terminology, although I imagine most of the time it was getting heard by Buddhists or at least Buddhist civilians, so to speak. But if you’re going to write a Buddhist poem in that traditional mode, then Buddhist vocabulary comes along with it. It was seeking to speak its truth, and I think, given a familiarity with its point of view, then that’s how it potentially lands.

The kind of poetic tradition you get out of China and Japan around this can sometimes take this in the whole opposite direction, where you’re trying to efface the author and the philosophical background so there’s just the poetic experience. Gary Snyder writes about asking a Chinese literary scholar who he thought was the greatest Buddhist poet in Chinese history, and the scholar gave him a name (I don’t remember what it was), but Snyder remarked, surprised: “But he’s not even Buddhist!” So the scholar thought that was more pure than anything more explicit, even someone like Tu Fu.

And then along those lines, what makes a poem “Buddhist” anyway? I don’t think there’s some formal parameter, but there could be all kinds of Buddhist “thinking,” for lack of a better term, that’s behind something that’s not explicitly saying “dharmakaya” or something. There are very few explicit Buddhist references in my book, Transmigration Suite, and if you didn’t know anything about it, you probably wouldn’t automatically guess anything about that as a non-Buddhist reader, at least unless you looked at the notes or the back cover. “Maze of Birth and Death,” which is most of the book, is a quite an extended Buddhist contemplation, but it’s not using Buddhist vocabulary and it is using western literary forms.

So I think you are free to write it in any way, from using all the terminology to carefully avoiding it, or using it playfully, like Jack Kerouac liked to do. It all seems legitimate–and even necessary–to me.

YEEEESSS- about that blog post exploring (let’s call it) Buddhistic revelation through Western poetic form. What am I even talking about? Come to think of it, I must be saying that with my westernized molded sensibilities I always attempt to create the multiverse of Buddhistic view. The western form is an interesting container for this, well, it’s the only container I have -except for those times that i leap out of it and do something very fresh, and that to me is the Buddha in the line. They co-emerge in my world at least ;).

There is a whole world of how one might think about what dharma in a poem would be, from traditional forms to the full on western avant-garde kind. I was taken up with this one a lot in my Naropa years, plus a lifetime of trying out this and that on the page. I think it will always be the case that art (in general) can succeed in communicating dharma if the underlying wakefulness shines through it in one way or another, whether there’s any connection to Buddhism per se.

Agree 🙂

Hello, Gary Allen:

Thank you for these thoughtful and informed blogs. I know almost nothing about The Doha, so please forgive me if I write anything ignorant or inappropriate.

My background is in poetry and as a reader of two languages (English and Spanish). I have developed an interest in reading Buddhist texts after six years participating in a Tao study involving several different translations. I would actually appreciate guidance on where to begin with choosing translations of Buddhist texts..

I appreciate what you’ve written about concision and also what you wrote previously about the rhythm of the language being as important to the translation as the precision of meaning. The lyrical qualities of a poem cannot be divorced from its meaning. I wonder, of course, if we are even capable of understanding those original qualities in languages and cultures that are foreign to us.

But perhaps I miss the point. Everything we read, see, hear, or remember is a translation of some sort (eg: the minute a moment passes we are translating it into narrative) and much is lost in the liminal space. This is why such thoughtful reflection on translation is important. The purity of the text is impossible to achieve, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t aim for the closest experience possible to that of the original and/or its significance to contemporary life and what outlasts the fleeting hallmarks of any given time period. I’m thinking that’s what you’re suggesting when you end here with “isn’t the most important thing that we get the message?”

I look forward to reading some of your poems and would like to read some of your translations.

Thank you.

Hi, Pamela:

Thank you for your thoughtful response.

In the Tibetan tradition, there were many translators, but three were particularly famous: Drokmi Lotsawa, Marpa Lotsawa, and Go Lotsawa. Lotsawa means “translator,” and they got it as a title of high status. So it wasn’t a diminished thing, like it tends to be for us, or something that was of small consequence. I think it implies that they didn’t just know the grammar or technicalities of translation. To translate was to transmit the dharma. They had to also know the deep meaning, beyond language.

Nevertheless, despite being a tradition rather acutely aware of the limitations of language, Buddhism has no problem with translation. It does get that you have to understand it within the confines of your culture and your time and space. Translation is necessary. But as I tried to point out, it still matters that you have some feeling for dakinis if you’re going to translate what they have to say.

I do think there’s only so much you can do from the literary angle I’m taking on it in these posts. Since I do have to read my way through stacks of Buddhist translations, you’re getting here my bardic reaction to a lot of what I’ve read, and I have done a lot of versions of those poems this way myself. If you want to read one of them, there are excerpts on this website from a dharma book I’ve been writing for 18 years now (no end in sight). There is one poem there I did from Naropa, a text blessed with a lot of vivid imagery. It’s at the end of the second dakini story. Here’s the link, under “Other Works” on the tabs at the top of the page.

I’ll write you an email about books you might read.

And I read just today, in Aspects of Buddhism in Indian History by L.M. Joshi, this sentence: “The Buddha’s injunction to his disciples to learn the sacred word [ie, dharma] in their own languages…was fully carried out by the faithful Buddhists.” Well, there you have it, from the Man himself. He always saw that the teaching should find expression in the local language and be used in the local language. This is different than attitudes toward, say, “sacred languages” of Sanskrit and Latin, quite deliberately held back by clergy from knowledge by the rank and file. Our job in English has to be an extended effort this way. Tibetans managed to get the main corpus of Indian texts into Tibetan over some 3-400 years or more. We’ve really been mainly working on this one for about 50.