#28 TOWARD A POETICS OF TRANSLATING THE DOHA: Part Three—Jackals & Vultures Weep!

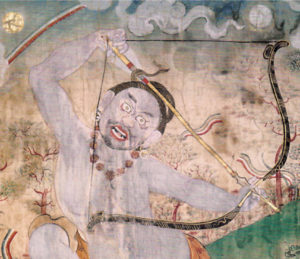

Shavaripa hunts the nature of mind.

Now, to put this thinking to the test, I’ll assay a fairly difficult doha by Shabarapada (aka, “Shabara,” “Shavara,” “Shavaripa”) from the Charyagiti, a collection of condensed, gnomically esoteric ejaculations by Indian siddhas, that has a detailed commentary by one Munidatta, without which I doubt we’d have the slightest idea what most of them have to say. Neither would I be able to do anything with them without Per Kvaerne’s study, An Anthology of Buddhist Songs (1977/1986), nor Sounds of Innate Freedom (2021) by Karl Brunholzl that collects the same material with full translations of the poems.

We may wonder who Shabara was, but much like the poems themselves, that information remains hard to nail down. “Wild-assed pagans” (as Peter Lamborn Wilson might describe them), the Indian Brahmanical system deemed “the Shabara” tribe outcastes, and the one clear story we have associates “Shabara” with hunting. Sometimes he’s identified as Saraha’s student, sometimes Saraha gets identified as “Shabara,” or quite possibly some upper caste yogi took on a Shabara persona as a way to jettison all the bullshit that comes with Indian high culture.

Here’s what he had to say, in my rendering:

SONG 50

The heart’s a spade in the entangled garden in the sky of the sky,

& the delightful girl awakening at my neck uproots it!

Shed, shed ignorant illusion, the disagreeable bitch!

Engaged in love play, Shabara takes the lovely maiden.

O, my overgrown garden equals the sky,

the white cotton flower in bloom.

At garden’s edge, golden corn comes forth,

dispelling the darkness, & the sky blossoms.

Millet ripens, & Shabara & Shabari get drunk.

Every day, Shabara thinks of nothing, lost in bliss!

Four bamboo poles bound together, attached with bamboo strips–

held by that, Shabara burns–& jackals & vultures weep!

Stupefied by the world, he’s murdered!–O!– as offering

to the ten directions!

Shabara enters nirvana, his state of Shabara removed–

What the hell’s he talking about? I’ll go through it, commenting on its meaning and the aesthetic choices involved.

Maybe the hardest line in the poem comes first. Munidatta explains the images there as the “four voids,” i.e., empty, very empty, great emptiness, and all-emptiness–though Munidatta labels the last “luminosity.” The four voids, otherwise known as the “four stages of bliss,” refer to identifiable phases of yogic experience in the practice of inner heat. The raising of fire in the central channel of the subtle body and descent of bliss from the crown chakra induces these four stages of ever more subtle, profound experience, the last the most profound and fundamental.

Thus, in the original, they come in this order: sky, sky, overgrown garden, heart’s spade. I’ve followed Brunholzl’s rearrangement just because I couldn’t easily get it to make sense without becoming really wordy. It’s still stretched beyond my comfort zone, but at least it makes an image you can in some way see and make some kind of sense of. Following Berrigan’s dictum about the line being fundamental to the poem, I think you’ve got to get something out of it, though it may not clarify everything you’d like to know. If you consider the images given for emptiness here, it does make some sense that there’s sky (an empty space), and that space of sky could get bigger, emptier, and then within that, “the entangled garden,” or all of samsaric relative phenomena, becomes pervaded in emptiness, but finally, getting down to the essence of the matter is the luminous wisdom at the heart of things, the spade that can dig it all up completely.

Whew! That’s one line.

Nairatmya, the delightful girl!

“The delightful girl” here references Nairatmya, “selflessness,” and otherwise the blue dakini consort of buddha Hevajra. “The neck” connects to the throat chakra, so suddenly we’re not at the heart center anymore, but in a different subtle body zone. Without explanation, the opening of the throat chakra gets related to the consort practice—which could be visualized and symbolic, or actual and literal—as a dimension of above mentioned inner heat yoga, and this functions as well to “uproot” that “entangled garden” of phenomena.

Already we’re drawn into a number of areas: emptiness, inward fire, the natural world and the fertile growth of the natural world, liberative eroticism, the subtle body.

The next couplet continues the erotic/romantic trope, contrasting illusory samsara, personified as an unhappy, difficult relationship, with a fetching, erotically satisfying lover. We could say coemergent ignorance vs. coemergent bliss, or the arising of the complications and struggles which come from falling into ignorance left for the beauties of nirvana and the arising of phenomena as wisdom-emptiness. In the aesthetic choice I made here, “disagreeable bitch,” I chose against the “shrew” and “harridan” of the other translators. If we’re using American English, when was the last time you heard the couple next door in bitter argument, and the guy bellows, “Go from me, thou harridan!” I think it more likely that we’re meant to feel the intensity of this as current experience, not the antique kind.

The next couplet, by following on the previous one, returns us to the earth, to the garden, thereby implicating spiritual experience, eros, and natural world fecundity together. The essential, esoteric meaning again identifies the garden with the third void, great emptiness that “equals the sky,” transformed into the fourth void of luminosity-emptiness. That’s given an explicit image here of “the white cotton flower in bloom”—the mind has come to final fruition of pristine wisdom with the full advent of the fourth void.

The third couplet reiterates and elaborates on the second, as “golden corn” appears on the boundary of that problematic garden. According to Munidatta, this corn symbolizes the “moon of wisdom” radiating light into the entangling, ever-propagating circumstances of samsara, thus “the sky blossoms” with the luminosity-emptiness of the fourth void.

I haven’t said a lot about it, but it’s hard to write good poetry without images that can land with the reader. I’ve focused a lot on melopeia. Ezra Pound broke down poetic effect into three principles: 1) melopoeia, or its sound; 2) phanopoeia, its image; and 3) logopoeia, the area of meaning. I think translators most easily land on the meaning angle and can miss the value in sound and image. Poetry then devolves into explanatory prose.

The doha tradition rides its inclination to strong, sometimes enigmatic imagery. This one furthers the luminosity theme, its clear, earthly images turning ethereal:

At garden’s edge, golden corn comes forth,

dispelling the darkness, & the sky blossoms.

This version of the garden image for samsara becomes “darkness,” or just silhouettes, shadows in twilight, re-iterating “ignorant illusion.” It’s like Adam and Eve never left that illustrious garden in the sky, but instead got lost in it, unable to see out of its infinite maze until it’s just so much groping in dreams in the dark. The “golden corn” invokes luminous wisdom expanding beyond the sky, again describing the fourth void.

It’s wonderful to carve out the words in shorter, more concise lines. That’s the kind of struggle you have to go through to translate poetry. If the imagery lands, the lines taut (no unnecessary words), and it hits a rhythm you can feel, all these things help bring the meaning home. Do it right, there will be layers of meaning, and you’ll fulfill Pound’s sound, image, and meaning dictum. That’s what makes poetry, poetry, and that’s what makes you feel, envision, and understand when you read it.

The next couplet begins with a phrase—“Millet ripens”—furthering the plethora of agricultural images. It’s meant, in fact, to describe the complete ripening of the fourth void as bliss. Munidatta explicates the symbolism as the ordinary bliss of “conventional bodhichitta” (Sanskrit: “awakened heart”) transforming into the unconditional “great bliss” of luminosity. Shabara likely chose millet as it can be used to make alcohol. The line finishes with Shabara and his consort, Shabari, drunk—by implication—on coemergent bliss, meaning that the subject/object duality of male and female has melted into the intoxication of nonduality. Those names, “Shabara & Shabari,” uphold the outcaste strata of Indian society as spiritual ideals, thus the usual thumbing of the vajrayana nose at a more usual upper caste pairing of male and female ideals, like Rama and Sita of the Hindu Ramayana. The discursive basis of samsara has been ravished away in the arms of the wisdom consort, thus Shabara dwells undistractedly in great bliss: “Every day Shabara thinks of nothing…”

Next we get the difficult image of “four bamboo poles bound together, attached with bamboo strips.” Relying on Munidatta, the “four bamboo poles” again represent the four voids and/or the four stages of bliss, while the “pole” imagery likely implies the subtle body’s central channel. The “bamboo strips” “attached” to the poles he describes as the senses and their objects (the eye and what it sees, etc.), in other words, the body layered around the central channel. The process of inner fire that induces those four stages, consuming the body (and whatever attachments come with it) as a “self,” thereby bringing Shabara to deathlessness and frustrating charnel ground predators waiting to make a meal of his existence.

Aesthetic note: We might reflect that jackals and vultures, whatever their feelings, aren’t given to a lot of sentimentality, but in the poem, they “weep,” as samsara will never dine on the siddha’s transcendent reality and reduce it to yet another morsel of birth and death. Within the boundaries of the poem, something unbounded happens that can’t happen normally—the proper place for saying such a thing.

We now reach the climactic moment of the poem, and here I felt I had no choice but to let the line spill over into extra words, but it’s describing the moment of spilling over!

Stupefied by the world, he’s murdered!–O!– as offering

to the ten directions!

“Stupified by the world” continues the idea of attachment to the senses, lost in the entangling, proliferating garden of phenomena, but, according to Munidatta, “the king of the mind” has made the illusory appearances “disappear through the sword of the true guru’s words.” Munidatta’s commentary emphasizes throughout the importance of the guru to the accomplishments depicted in the poem, though Shabara seems to make no reference this way. I went with “murdered” over “killed,” as this seems more in keeping with the expression of tantric intensity. Wisdom has destroyed the “’I’ and ‘mine’” of ego-clinging, as the ultimate oblation to the universe (“the ten directions”) and reality itself. Thus “nirvana,” (“extinguishment”) ensues, finally removing “the latent tendencies of ignorance,” i.e., Shabara’s ego or the “state of Shabara” dissolves to nothing.

In fourteen lines, Shabara’s doha describes final yogic attainment, done with the siddhas’ evocative panache. He synthesizes subtle body inner heat practice with vegetative fecundity, drunkenness, and eros, shifting them all out of their normal cultural parameters into the nondual tantric realm. Especially he uses the poem to explicate the experience of attaining the fourth void, its union of subject and object, its luminous heart, and its abiding bliss. It’s a tall order, I’ll allow, to translate this effectively into English or any other modern, western language. The reader’s got to feel the impact of what he has to say, or you’ve missed the mark. Of course, his poetic language doesn’t easily allow for you to get into its packed meaning (though I wonder how his original listeners received it?), which subsequently takes pages of explanation. But this, translators, is what you’re up against. You have here a poem that unfolds vistas to the final stage of arriving at the primordial, inseparable bliss, luminosity, and emptiness. The bard has declared his freedom from caste and spiritual strictures, and in his final flourish, from being the speaker of the poem himself, vanishing, “the state of Shabara removed—”

Shabara & Shabari, carved from rock.

Hello Gary:

Thank you so much for sending me your blog writings…. I really appreciate how you have illuminated for the reader, the poetry of this doha. I feel this doha quite deeply. with gratitude, janneli

Dan Hessey did his own version of this based on mine. I think you can see what happens when you bend the translation toward a more interpretive language, you can connect it up in a way that’s less available if you’re being literal (my version, comparatively, is more literal to the original). But then, as I’ve been saying, it’s still important that the lines find a way to land with the reader, so this is a way to help that along.

Brilliant-sky, mind-sky, dense growth and a shovel;

Our passionate embrace can dig all this out.

By releasing the cruel consort, ignorance’s

Fake face, I, Shabara, can make love

To my eternally ravishing consort.

Now my weedy overgrown garden is the sky’s

Pristine cotton-blossom blooming;

At the boundary of this weedy plot

Radiant golden corn grows;

As gloom retreats, the sky blossoms.

Our millet has ripened, and fermented,

Shabhara and Shabari are so drunk!

All day long Shabara’s non-thought is bliss.

Four bamboo poles bound by bamboo strips

Are Shabara’s pyre. Jackals and vultures

Cry and howl as I burn up utterly.

Dumfounded by this world, “Shabhara” is incinerated

And offered to the ten directions:

As “Shabara” dissolves, “Shabara” is fully freed.