#49 ROCK APOTHEOSIS: Becoming Led Zeppelin

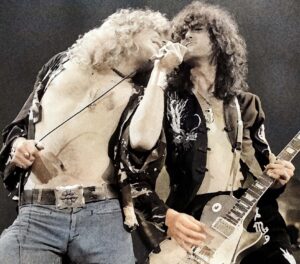

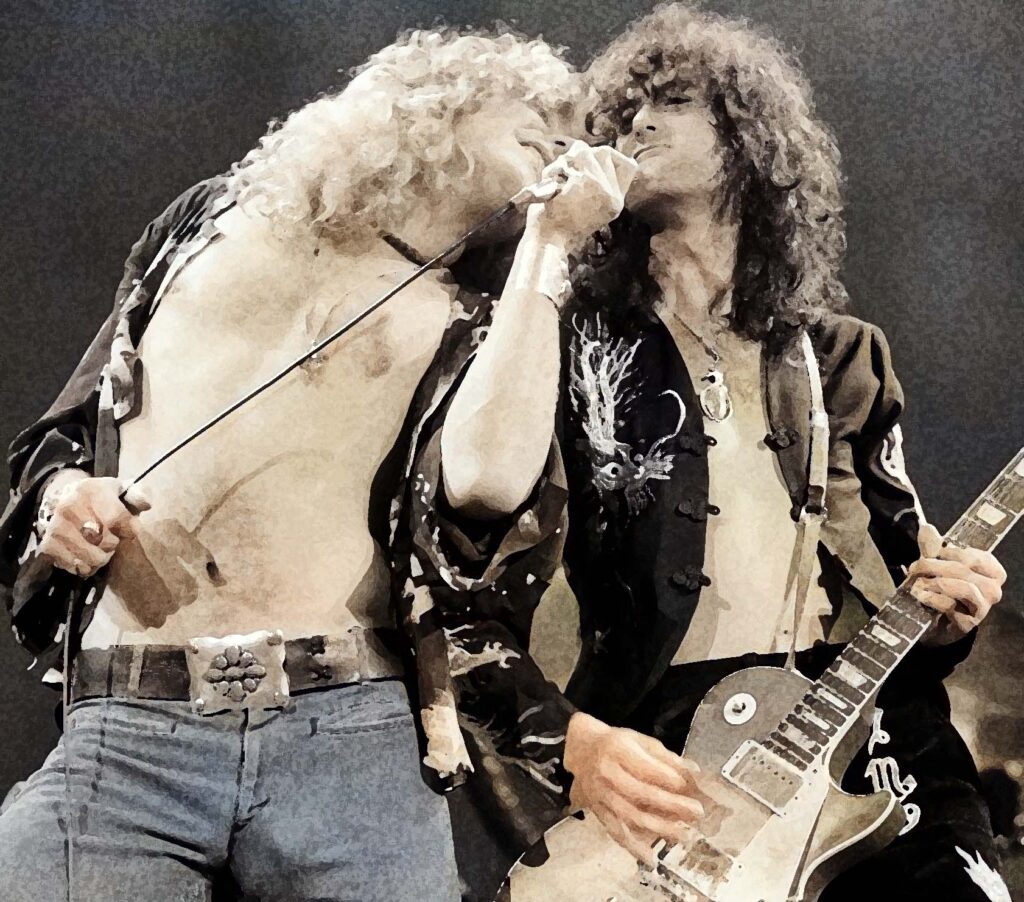

Plant & Page: front men

I’ve been writing this long poem (80 plus pages as of this date) about poets and poetry (and anything else that crosses my mind). It’s returned my attention to creating art, the process of it, and what that is or isn’t. While this historical moment has largely obviated any centrality in the greater social consciousness to poets of the written page, it has raised musicians and movie actors to global profile.

That’s certainly what Led Zeppelin had in their day, forming in 1968 to burn across the firmament until the untimely death of their drummer, John Bonham, in 1980. Becoming Led Zeppelin (2025), directed by Bernard McMahon, charts the four players’ early lives until their convergence as a band on through the recording of their first two especially great heavy metal albums, landmarks of the early genre.

I have all their studio albums and know the story. I’ve read, of course, Hammer of the Gods (1985) by Stephen Davis, a classic account of a classic rock band. But they weren’t anything resembling “classic” when they started out. It’s more like they blew a screaming hole in the rock world.

And that’s something of what I hoped to see in this movie—Led Zep in their youthful testosterone high prime. It did clarify some things for me about how they became this mythic force, including the rock world they grew up with circa 1958-60. The bands then (English ones in the film I’ve never heard of) did aim to get you to rock back and forth in your seat, featuring guitar solos that I might have dismissed in my youth, but listening to them carefully now, you hear a nimble joy in how they’re bending their notes. The guitar players were getting off! This music was never going to fill stadiums, and yet it’s precisely here that the school boy future band members perked up and took note. British white boy rockers had absorbed American rock’n’roll and black blues music, and started to turn it into at least part-time jobs.

A couple days after I saw Becoming Led Zeppelin in the theater, I happened upon A Hard Day’s Night (1964) on TV, a fictional movie the Beatles made about themselves as they were sky-rocketing to their own fame. They of course were the band that made rock into a world phenomenon, and initiated about a four year period where young women screamed their heads off and chased popular musicians down the street. (On this stimulated unleashing of raw energy by someone who experienced it: “It’s a powerful thing,” Keith Richards observed, simply enough.) I saw the Beatles that same year on the Ed Sullivan Show myself (73 million viewers!), playing through a barrage of female ululation, and somehow America was never the same.

But, well, why? Listening to them on A Hard Day’s Night, the rhythm had become more pronounced. You could bop up and down with all those out-of-their-minds teen girls. You can’t make much of the anodyne pop love song lyrics, but they’re delivered with potent harmonies by four cute boys, and when they reach the climactic song, “She Loves You,” it ain’t the brilliance of the lyrics that gets them swooning, but how the lads’ voices land on the “Yeah, yeah, yeahs,” hitting a deeper, wilder tone at the end, which I finally understood, despite the sweet, harmless romance of the lyrics, you can feel the salaciousness of. The sound of that wasn’t anything anyone had heard before on their radios or TV sets. It released something waiting to get out.

Allen Ginsberg thought that the whole development of rock pointed to the awakening of kundalini life-force in the muladhara chakra at the base of the spine in the modern West. He considered it a return to the body and freeing of repressed physical consciousness.

Be that as it may, it’s still quite extraordinary what happens by four years later.

None of what was to come with Led Zeppelin would ever have arrived without Jimmy Page, whom we see in his elementary school uniform with a big smile on his face and his first guitar. That seems modest and endearing enough, but largely self-taught, he dropped out of school by 16 to become a full-time professional session musician. John Paul Jones, who similarly came up through the pro ranks as a session player on bass and keyboards, explains in the movie that they had to learn their parts the night before and play them without mistake at the studio the following day, or they would not continue to get hired. Thus for both of them, they pursued the rigors of constant practice married to ever changing styles, training them in all manners of music, including Muzak.

That was his apprenticeship, and it goes some way toward explaining the fluid, multiplicitous directions he could go in a single guitar solo. Starts to, anyway (I’ll come back to this).

But also his interest in the sound board proved consequential. He describes himself asking what this knob and that knob did from the producers and engineers he worked with, essentially teaching himself about the potentials of how to shape sound. Here he seems particularly thoughtful and engaged. He knew already much about how major rock bands of that time achieved their own sounds, working in sessions with the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, the Who, and others. When he talks about this in the film, you get a sense that he had a full vision of the sonic dynamism he wanted by the time of recording the first Zeppelin album, and he already knew before the second where he intended to take it.

And yet another important element to what happened came out of his many years in the music world, also playing in bands, including one famous for employing him, Eric Clapton, and Jeff Beck, the three best Brit guitarists of the era (the obligatory Yardbirds reference). Thus he had an encompassing set of musical chops, skill and inspiration as a producer, and a familiarity with the business side of music, the money and the management. Unlike so many others, he didn’t form his own band with starry-eyed naiveté; he knew what he wanted and found himself in a position to get it. As an artist, he apprenticed in all these dimensions and emerged still young, revved up, and wanting a band who could realize his vision.

That’s what I take to be the crucial karmic ingredient, and yet it couldn’t have found fruition without the unusual magic that arrived when the four players got into a room for the first time and instantly knew they had something. Page pulled in Jones, got Robert Plant on howling vocals, who brought in Bonham on sharp, driving drums. By instinct, they knew how to both wail away and leave enough space for the other band members to play in. Page did not have the problem Jimi Hendrix had with the Experience, especially his bassist Noel Redding who simply couldn’t keep up with his wizardry. The Zeppelin musicians had a special sensitivity while setting the standard for fast, aggressive, HEAVY guitar music that also allowed them to turn on a dime, if they chose, and exuberantly improvise. Suddenly, they were something and could feel it.

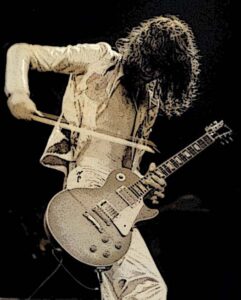

Page: Inspired to attack his guitar

(I wonder also about the karma the four of them had from their previous lives that brought them so fully ripe to create together.)

Not that the world was entirely ready for them, as evidenced in the film by an early gig where it appeared English families had come out to hear some music entertainment at the local gym or something. Little boys cover their ears from the loudness, and moms sit there with sour expressions on their faces. You call that music? That’s just noise!

On an interesting side note (not mentioned in the film), Led Zeppelin got pitched to Mick Jagger as a band for their 1968 TV special, “The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus,” but he demurred, clearly not thinking much of their sound, despite how they drew in their early days from the blues just like the Stones had. They were, perhaps—ironically—too loud and noisy for his taste.

Page had the money to pay for recording their first album, producing it himself, sparing them record company machinations. They put out a classic (Led Zeppelin I, 1969) of blues souped up into another dimension with Plant’s incredible, visceral vocal range, enormous power chords, and scorching solos. Atlantic Records, a giant company of the era, consented to giving them complete creative control, freedom from the need to put out singles, and a historic amount of money, and then they hit the road.

And here’s where I got some of what I was most hoping for from the movie, Zep with all the live sizzle and Page in effortless, intricate mastery over his inventive, blowtorch solos. WOW! Who nowadays plays this well? Jack White, maybe? Anyone?

Page credibly plays his guitar with a violin bow, among many other pyrotechnics. But the band amazingly hangs with him—fervent, fast, electrifying, and in your face! That thing hiding in rock music, that lion or chimera, really gets let out of its cage here. Maybe getting chased down the street had receded, but fronted by long-haired pretty boys Plant and Page, it’s not hard to see why young women were soon throwing themselves at their feet. Off to America to grind it out with nearly nightly touring, their reputation quickly ascended, and the release of their first couple albums cemented it within a year.

The movie uses some footage from the era put to the album recordings like a music video, apparently not having the sound, or sound that couldn’t be cleaned up enough. This works best when they go into flashing full color mode on the extended psychedelic bridge of “Whole Lotta Love” (Led Zeppelin II, 1969). The band interviews, criticized by some as “boring,” really just focus on the essentials of the music, and likely out of exhaustion, they didn’t care to address their own mythological gossip about mud sharks and groupies and satanism. They might have had a little more spark if the filmmaker had put them in the room talking to each other. That’s somewhat mysteriously absent. (Are intra-band politics still at work for these old guys?).

You can guess, since Jones was married, and both Plant and Bonham produced wives and babies practically on the way out of town to their first gigs, that maybe quite a lot of melodrama was on the way. Plant, who’d been homelessly sofa-surfing for a couple of years, and now a dad, would soon grind his hips and raise the hair on the backs of necks with his banshee voice at center stage, turning into the “golden god,” something art can confer on you. It might also drug you, lionize you into a big ego, and outright kill you by 32, as it did Bonham who, like Hendrix, succumbed asphyxiated by his own vomit.

But the movie doesn’t follow the band through its later legend of epic partying or exploratory artistic achievements and failures. It does put across a feeling that something special and enormous would happen whenever they stepped into the open space of the stage, and shows you how they caught lightning in a bottle, practically leaping from a cliff to do it.

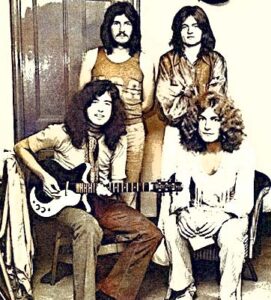

Becoming Led Zeppelin in the same room at the same time

No Comments