#32 ELEGY FOR WINNING TIME

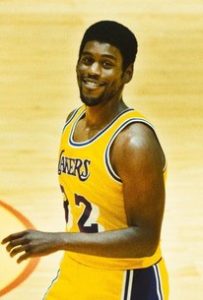

Quincy Isaiah as Magic Johnson in Winning Time

The last episode of Winning Time’s second season on HBO charts the 1984 NBA finals between Magic Johnson’s LA Lakers and Larry Bird’s Boston Celtics, an animosity great enough for the Boston fans to pummel the Laker’s bus in a flurry of garbage as it pulled out of Boston Garden. In a signature brutal moment in sports history, late in the pivotal game four, Kevin McHale clotheslines Kurt Rambis while he goes in for a layup, catching him around the throat and flinging him to the floor. Do that nowadays and you’d be ejected, fined a hefty sum, and get suspended for multiple games. Back then, it was what you’d call a “hard foul,” but it’s something Winning Time makes you feel as it happens.

It’s great story-telling craft, how the show puts you in that highly charged, highly combustible atmosphere and lets you feel it like you’re on the floor with them. They’d been building up to this for two seasons. Game Seven supposedly ends with Lakers actually getting into fist fights with fans who poured onto the floor.

I’m reminded of a conversation I had with an old Fox News-watching friend I’d grown up with in Vermont and hadn’t seen for decades. I happened to trash Rush Limbaugh, and this definitely upset him, but when I said I liked the Lakers (I’d lived out west my whole adult life, and this was the Phil Jackson-Kobe-Shaq era Lakers), that’s what really pissed him off.

When the Lakers lost game six and the Celtics continued to push them around and “out-physical” them (in current euphemism), we enter their dead silent locker room afterward, watch Pat Riley (Adrien Brody) go into his office, proceed to trash it as the Lakers listen to things crash, then come out composed enough to give them an invigorating vision for how to win game seven, which they then go into with great inspiration…to lose.

And there you see it, Magic Johnson (Quincy Isaiah), slumped alone under the shower, in abject misery, not only from losing the finals, but losing it to hated rivals.

That image cuts to Jerry Buss (a terrific, Emmy-worthy John C. Reilly), the Lakers owner, with his daughter, Jeanie (Hadley Robinson), lying on their backs at center court, talking in an empty, post-season arena. He says that she’ll one day be the owner of the Lakers—a female owner, something unusual if not completely missing from professional sports in 1984—reassuring her that all will be well. Then we cut to a series of written descriptions about what happened to the different players, the franchise, the owners—a list of triumphs, really—and the credits roll.

What? I leaned forward on the couch in shock. Did they cancel the show? They must have. Why else would you end “Winning Time” at a moment of catastrophic defeat?

Well, an expensive show, it didn’t get the ratings. I had one of those classic moments of misery myself, when one of your very favorite shows hits the dustbin just as its cranking up to show you greatness.

That’s what I found fascinating. All these people who play a central part here in the dynasty-making—Jerry West, Pat Riley, Jerry Buss, Magic, Kareem—they’re practically mythological nowadays, despite all of them still alive (except Buss) and still appearing in the media. Part of the show’s craft has been to give you a sense of Los Angeles in the 80s at a remove—using old video footage or shooting current footage and making it look like old video footage for establishing shots and transitions. They took the time to recreate the look and flavor of the Boston Garden. They even got Jerry Buss’s tailor to help dress Reilly in the part. It feels and lives like an older world and a time that’s past.

You see that in the white ownership and white management in their offices, and the predominantly black locker room. You are seeing society, not just basketball. The show isn’t tracking the established dynasty—it shows you the dynasty in making, warts and all, and hence doesn’t spare the characters in the tale, no matter how legendary and hall of fame bronzed they eventually become. You can easily understand why the actual people here like Magic, Kareem, and West don’t like their portrayals. Normally a sports fan only saw their excellence on the court. You didn’t see Magic Johnson, young, charismatic, relatively rich, and out beyond his Seventh Day Adventist mother’s strict regard, searching for booty and regularly finding it in Sin City. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s lifetime scoring record stood until this past year when Lebron James finally broke it; what you didn’t necessarily see was his rather dour, introverted, brooding and contemplative kind of personality (played with nuance by Solomon Hughes). Jerry West (Jason Clarke), himself one of the great scorers in NBA history and a tremendous success as an NBA general manager, goes all hot-headed behind the scenes, as winning and losing seem like life and death.

You can stop about here and object that maybe this isn’t all that accurate, as the people themselves have been insisting. I don’t know; I wasn’t there. I have a feeling that even if I was, I wouldn’t always know or agree about what did and didn’t happen. It’s mega-researched, while also fictionalized as convenient to the story-telling. What I get more as a viewer comes from the lived lives you witness. At the beginning of the first season, Magic, coming off winning the national college championship over Larry Bird’s Indiana State Sycamores, arrives at the Lakers as the No. One pick in the draft. His infectious, joyful smile—something Isaiah wonderfully radiates—has to contend with Kareem’s now grizzled, jaded veteran, who immediately asserts pecking order and continuously calls him “rook.” That smile—fortunately innate, quite buoyant, and clearly not explainable as “good genes” inherited from his severe mother—must struggle uphill through the moody clouds on Kareem’s mountaintop.

Solomon Hughes as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

It’s all a struggle, all those plot-lines, like how Riley goes from bored, itchy, retired player, to inept color commentator with announcer Chick Hearn, to assistant coach, to getting handed the keys to the Cadillac as head coach on the other side of coaching searches (this includes a dead body!) and a lot of strained internal politics. In a great moment, the successful team he inherits continues to lose, and he must lose his easy going, well-liked assistant coach persona for a strident, truth-telling, fiery sermon in the locker room, finding the life-giving chi of the head coach’s voice.

That’s the kind of thing that held me rapt with this show. You got to see process, not just the trophy in the case.

Larry Bird comes into the league with Magic Johnson, and initially, as the show paints it, as the darling of the sporting press and NBA coverage, while Johnson looks on, flummoxed why they’re not more interested in him. Bird wins rookie of the year, but Magic wins that season’s championship over Philadelphia. Bird, as prickly a competitor as ever played in the NBA (until the advent of Michael Jordan), must endure watching those particular finals with a beer in front of the TV at his mom’s house in French Lick, Indiana. Thus, skillfully, the show suggests the many more ordinary moments of how they rub against each other in a continual psychological and athletic creative friction that dominated the NBA in the 80s, and raised it as a sports league to greatness.

The show parallels the effort on the court with Buss’s efforts to make basketball snazzy enough to attract LA’s glitzy elite (a couple of those modifications: adding a glammed up night club to the arena and sexing up the cheerleaders for less rah-rah and more bump and grind). He develops his own conflict with the Celtics through a rivalry with cigar-chomping Red Auerbach, at that point the Celtic’s president. Auerbach regards Buss as a flash in the pan, but Buss is out to transform the league itself. At the same time, one of many details I didn’t know was how much he hung on the financial edge in the beginning, getting stern lectures from his mom (Sally Fields—one of many good acting choices) who does the books, and by second season, his wife suing for divorce and wanting a hundred million dollar settlement.

We never do find out how that divorce resolved, thanks to the show’s cancellation. It’s one of many threads going that somehow, somewhat miraculously, added up to one of the greatest dynasties in sports. Winning Time, with its many creative camera angles to make its players look tall enough, all its raw looks at human foibles, its buoyant and inventive approach (even having characters address the camera directly), made for a lively adventure into the sports world, God bless ‘em. May Winning Time rest in peace, and may someone come along with the same kind of verve and pick up where they left off.

Bird & Magic in dynastic conflict.

No Comments