#35 DHARMA EYE—Part One: Seeing the Sacred in the Ordinary

Three lovely Korean ladies in traditional hanbok, at the Chongmyo Royal Shrine, 1995

I arrived in South Korea in September 1995, and I’d been there 3-4 months. I started to think about my camera, a beloved Minolta 35 mm. film camera I’d had by then for about ten years. I hadn’t put it to use, but here I was in a perceptual world quite distinct from my lifelong American one. I told myself I’d finally go out and take pictures that Saturday.

I woke up Saturday morning likely slowed with what had become the standard hard drinking English teacher Friday night. I don’t think I got out the door until the afternoon. I couldn’t then and can’t now explain why I was in such a bitterly disaffected mood, but I do remember going down the sidewalk as I passed three school boys in uniform coming the other way. Through no fault at all of their own, I wanted to smack each one of them, practically vibrating with fury. I somehow kept my composure and went down on the bus to Jongno in the area where I worked, and started taking pictures.

That’s when the magic descended. I couldn’t very well stew in my kleshas (Sanskrit: “afflictive emotions”) and look into the viewer at Seoul, aiming to crystallize my perceptions while maintaining my gargantuan internal pissiness. So, in fact, I did start looking out through the lens and took some of my first vivid pictures of Korea. When I finally rode the bus back to my apartment, I felt ecstatic. The process had transformed my head space utterly.

It’s at that moment, though I’d always liked taking photographs, that I got more serious. I had this (to me) exotic world, and I took endless pictures of Korea and Asia at large. It was about here that it became a second art for me.

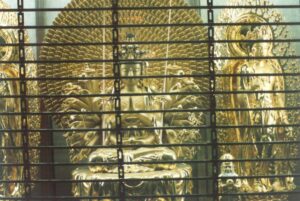

Nirvana as seen from samsara

That experience made perfect sense from a meditative viewpoint: I had brought my mind to my senses in the present moment and synchronized them together through the medium of photographic art. I forgot about my highly intensified mental aggression, and it evaporated in the sunlight of sensory awareness.

Korean forsythia

I had an interest in the past of trying to photograph the vibrancy of trees and bushes, and I subsequently strolled deep down this avenue in Korea, one I’ve explored ever since. As I’ve said before in this space, I seem to have a particular fixation on photographing especially trees, but it’s in no way philosophical or some insistence on nature as the proper subject. I do it for my own joy, first and foremost. I never seem to tire of exploring it. But others have liked some of these pictures, which also contributes to my joy, so…win/win!

Allen Ginsberg also took up photography as a secondary art, and while an important mentor for me, his style focused on people in a rich black and white. Talking about Jack Kerouac in connection to his sense of photography, he said, “It’s the notion of sacramental documentation, and of using the raw material of your own actual experience in your work, whether it fits accepted aesthetics or not. This theme is very clear in Kerouac’s books—the motif of sacredness of the world” (Snapshot Poetics, 1989).

He developed a sensibility that joined his poetic aesthetics rooted in American poets Pound and Williams to the practice of framing a moment, “ordinary” or not. The framing or articulating comprises the process of art, and then the most ordinary kind of thing—much like the Zen aesthetic in haiku—finds its magic exposed and retained within the artistic medium.

Consider this haiku from Basho:

Wrapping the rice cakes

with one hand,

she fingers back her hair.

He’s ostensibly admiring her dexterity, but what stands out is the tender sensitivity implied in the gesture of moving her hair away. This seems photographic, though it’s a good couple of centuries before cameras show up.

Tongdaemun Market, Seoul

Of course nowadays cameras—and pretty sophisticated ones with triple lenses–get used to record the most ordinary things, like multiple angles on today’s lunch. Good grief, is anything not photographed? You can’t even walk down the damn street without it happening sometimes. But those are other sensibilities, both how fantastic my lunch was and the prerogatives of the security state.

Pusan Fish Market

I remember one of my students in Korea, a very nice young lady, who showed me her stack of photos from her trip to America, the theme of which consisted of the fact that she was in America. Hence she occupied each photo front and center: here I am in front of the Statue of Liberty; here I am in front of Macy’s; here I am in front of the bus station; etc. I don’t mean to denigrate her, but what was apparent to my aesthetic eye was that she never really saw America, presumably a compelling place. She saw herself in America, and that was the main point.

But unless you get out of the way, you don’t really see what you’re looking at. That I take to be a fundamental principle of dharma art, as Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche would describe it. Then there’s some hope of finding and revealing the sacred in the ordinary.

Fish market ladies

People might not like that word, “sacred.” It does conjure up all kinds of churchy connotations or sometimes cultural ones, like this is where Roger Maris got his 61st dinger on the hallowed ground of Yankee Stadium. But not here. We’re not excluding anything, bifurcating reality into sacred and profane. The whole logic of dharma art, in this sense, comes before any bifurcations or boxings up of the phenomenal world.

In other words, you see what you see in all its vividness, and that’s what sacred means. It comes before you can drag it into your storyline, merchandise it, or make it into a political football. In fact, that’s harder to do with ordinary things, like a branch or a rock or a squirrel.

That’s often what we don’t appreciate or even notice. We have too many big deal things on our agenda, and anything that falls outside its boundaries has no meaning.

Snake medicine store front

But that’s the irony of it all. In our self-importance we fail to see the sacred world we’re already in, already part of the fabric of. This relies on us waking up to our own perceptions. “The question of perception,” Trungpa Rinpoche says, “becomes very important, because perceptions can’t be packed down into a solid basis. Perceptions are shifty, and they continuously float in and out of our life….The idea is that when you describe an experience and relay it to somebody else, whatever you perceive at that moment sounds extremely full, vivid, and fantastic. But if you try to recapture the whole thing or to mimic it, it is impossible. You might end up philosophizing, going further and further from the realities, whatever they might be” (Dharma Art, 1996).

Seoul nightlife

You could do this with photography, if you’re too interested in some theoretical objects you “should” be capturing. That is, if you ask me, less fun than taking pictures as they suggest themselves to you perceptually. You’re trying to achieve something, and the “achieving” blocks the sensitivity to perception. It’s not different when you write creatively; in fact, it’s probably a lot worse due to all the baggage words can carry, not to mention their on-going involvement in dragging us into habitual thinking of all kinds. I trust the same thing goes on in other arts. Contemporary painting, for instance, seems enormously burdened with its critical history. It doesn’t have to be, of course, but study it and that’s likely what they stick you with.

The dharma eye sees perception nakedly, thus it has a degree of freshness, despite familiar subjects. Of course, one still has to find a way to put it into art, and there could be quite a demanding apprenticeship in craft when it comes to using words. Ginsberg liked to quote Robert Frank, a Swiss American photographer who mentored Ginsberg’s practice, calling it “the lazy man’s art.” Short of any elaborate staging, you can simply bring your eye to the world you’re in and see it fresh, with feeling, and click the shutter. It remains for you to put a frame around it in such a way that reveals what you see through your physical eye in your mind. That does require skill and discernment of some sort, and, just perhaps, a philosophy of the frame.

The statue of Admiral Yi contemplates the new Korea

Hi Gary, lovely post. I really appreciate it. Good to hear your voice again. Keep bringing it.

Wonderful photos! But too bad you didn’t get a selfie with Admiral Yi.

Thank you Gary for this insightful journey through the camera lens.

Wonderful photos Gary