#38 The Oppressiveness of Imperial Languages “& MEANWHILE” in Ukrainian

At our organization, Mindfulness Peace Project, where I work as the “Co-Executive Director,” the lion’s share of what we do consists of helping prison inmates to learn dharma. This has resulted in some cases in many year relationships with people I’ve never directly met, done entirely through writing personal letters and commenting on course work they do with us. This is how I’ve gotten familiar with the only Ukrainian I happen to know, Andrei Belei.

Andrei had the misfortune of getting drafted into the Soviet army in its Cold tug of War with the CIA in Angola. He came out of this—I’m inclined to say—of course traumatized, acting out, and coming to America, where he continued to act out badly enough that it landed him in life without parole courtesy of the State of California penal system at the age of 24, where he’s resided ever since.

After many years and a fat file full of letters, I sent him Transmigration Suite (2022), my magnum opus of poetic and Buddhist contemplation. Inspired by it, he wrote me saying—much to my delight!—that he wanted to translate it into Ukrainian. Now, if you’ve read some of the other things I’ve written about translation, you know I have opinions about this, but frankly, he uses better English than virtually any other inmate who writes us, despite it being one of three languages he knows. I’ve long thought what a tragedy that they sent him off to war. He properly should have been an English professor in some big university in Kiev. Instead, he gets to sleep in a bunk in a huge dorm in the most over-crowded prison system in the U.S.

Well, you live the life you live. Instead of a steady bourgeois academic one, he’s been on a long odyssey of violence, excruciating loss, and spiritual renewal. In the end, it’s not always clear what’s the good and what’s the bad.

What I didn’t grasp was that Ukrainian likely constituted the least practiced of his languages—an outcome of the Russian/Soviet domination of Ukraine, which began, well, Ukrainian history is a mess of interventions by foreign nations, but the formal Russian empire got its mitts on it circa the early 1700s. I wonder if there isn’t something especially pernicious about modern imperialism as it likes to go through the dominated culture with a fine tooth comb for finding ways to get it to knuckle under. Anyway, what I learned was that Ukrainian wasn’t Andrei’s primary language:

“OK, time for me to be entirely honest about my Ukrainian. I’m from a big city in eastern Ukraine, which means I grew up speaking Russian. At home, at school, everywhere except during Ukrainian classes and when we went to visit my grandmother. I was completely fluent in Ukrainian: read books when I had to, spoke when necessary. My father worked for a Ukrainian newspaper and was a bit of a nationalist, but at home we spoke Russian. Part of it was that the Soviets worked hard at destroying national cultures and languages, so for someone speaking Ukrainian was either a country bumpkin or an asshole radical from the West. And yet I was fluent and could have translated your book 35 years ago (aside from not yet having the knowledge and experience necessary to understand it, that is).”

Language has life insofar as you bestow it by using it. Otherwise it risks getting robbed of juice like a vine in desiccated soil, and if you apply this to how a language can saturate a national or tribal identity, the thumb of empire sees reason to come down and cut it off.

When I lived in Korea, my students told me about some academics who, in the 1920s during the Japanese fascist occupation, compiled a dictionary of Korean words and published it. For their efforts, the fascists kicked in the door and dragged them off to prison. To think in your own language, to remember its words, threatened the hostile language that had come in to control and recondition your tongue.

In downtown Seoul, in the Jongno area, where I worked, were three different palaces left from the displaced Korean dynasty. The Japanese came in, took over one of them, and built the central office building through which to administer its occupation of Korea. One of the first things I did in Korea was visit this place, at that point a kind of Korean national museum. The building itself the Japanese constructed, if seen from an aerial point of view, shaped the character for “Japan.” They’d stamped their imprimatur on Korea, right on the court of its own rulers. Curiously, the Koreans thought so well of the building—it is impressive in some way, it has a power—during the time I lived in Seoul (1995-6), they began work on removing it piece by piece from the palace grounds but building it again in a less invasive space.

But what really struck me reflected the precision and thoroughness of the Japanese national style: to subjugate the feng-shui of Korea–the drala, the geographic/spiritual chi of Korea–they went around to its many mountains and pounded huge metal spikes, many feet long, into the crowns of all those peaks. I must admit, I’m quite impressed by how much they meant business.

Though I suppose I’m not supposed to say it, here might be the fascination and attraction the dominated have for the seemingly superior empire that’s taken up residence. There’s much to be said about the reciprocity between them.

(And, I might as well add, that I had a job in Korea thanks to the British, which implanted English around the globe: “The sun never sets on the British empire!” Nobody speaks Korean anywhere else, so those ambitious Koreans, hot to make themselves known to the planet, established the national English industry, which employed me.)

Andrei:

“But then I came to America. Until February 24, 2022, Russian was the lingua franca of all ex-Soviet emigres, so that was what I was speaking when I wasn’t speaking English. Then I came to prison and for a couple of maximum-security decades had so little contact with the people from my past and with the outside world in general that it was almost all English all the time. V. Stus, one of the great Ukrainian poets you introduced me to (turns out he was in my much younger sister’s post-Soviet high school curriculum) ” [I sent Andrei some poems in Ukrainian and English] “wrote, ‘Homeland is where they understand you when you talk in your sleep.’ Well, for me that would be America.”

This reminds me of something Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes (1928-2012) liked to say (I’m paraphrasing from memory): “If you dream, make love, and curse in a language, that’s your native one.”

Mexican writer, Carlos Fuentes: making love, dreaming, & cursing

Dreaming, making love, & cursing (extensively) all have something to do with what makes poetry, poetry. Poetry’s finding your true native tongue, which is the only one where you get to say what you most need to say.

Thus Andrei lost a root in his native land, transplanted instead into a world of cement and razor-wire, until all the labyrinthine tribal animosities housed within became familiar. What exactly constitutes home when you’re continuously transmigrating scenarios, languages of all kinds? I can remember, for instance, when Korea seemed like home to me.

Andrei:

“It kills me that my Ukrainian went away, that I can’t translate your book or have a real conversation with my son. His linguistic upbringing was similar to mine, with Russian at home but more Ukrainian in the public sphere, but last year, like many of our people, he and his wife decided to stop speaking Russian altogether. He is kind about it, to the point where we text each other in English” [Andrei now has a tablet with limited internet in prison] “and he’s OK with me slipping into English or Russian when I try to talk about anything deeper than everyday banalities. But it really kills me that I have to do that (rather than use broken, Russified Ukrainian which we call ‘Surzhik’). Even knowing that I had difficulty accessing the language at conversation speed, I honestly thought that, with some help from a dictionary, I could translate on paper. Simple prose, maybe. Technical manuals, definitely. But good poetry…”

Come to think of it, this may be the first account I’ve heard of someone losing a language that had so many deep connections. You lose, as well, the world that goes with it. (Isn’t that what the relentless bombing of Ukraine has undergone in far more blunt terms?) A much closer example of this would be the American/Canadian attempts to strip away the languages of Native North Americans, take away their clothing, force them to convert to Christianity, etc.

However, on a more happy note, Andrei said he managed to translate the first three poems from Transmigration Suite, and he sent me a Ukrainian translation of “& Meanwhile.” This poem discusses how the divine world and the gods exist within the apparent, immediate one, as its own limitless interstice, found anywhere, no more or less exotic than a dragonfly’s wing.

Normally we’re trapped reaching for this immaculate and beautiful thing somewhere out beyond our fingertips. Perhaps we’re correct that it’s out there, but we don’t know how to see or truly invite it. It changes shape with the form our supplication takes. What we have to say to our own divinity–lost in translation. Nevertheless, we live to be electrified in that field, to see beyond habitual imaginings and the prisons they produce. If something of that seeps into the poem, then language lives and blossoms on the vine.

& MEANWHILE

Spiraling out

a crystal cavern,

or soaring without wings,

drinking from a crystalline stream

suspended by its own recognizance.

Taking this shape

or that, the same bliss.

Form determined by

the worshiping eye?

The observer, hung wriggling

in another sticky web, configures

the observed accordingly.

There one sings the divine

songs, like garbled echoes

scratching for purchase,

like choking words clutching

for a throat.

& meanwhile the gods

–neither massive

nor minuscule,

perfect in their own worlds–

rest in the interstices

of a dragonfly wing,

a transparency without a bottom.

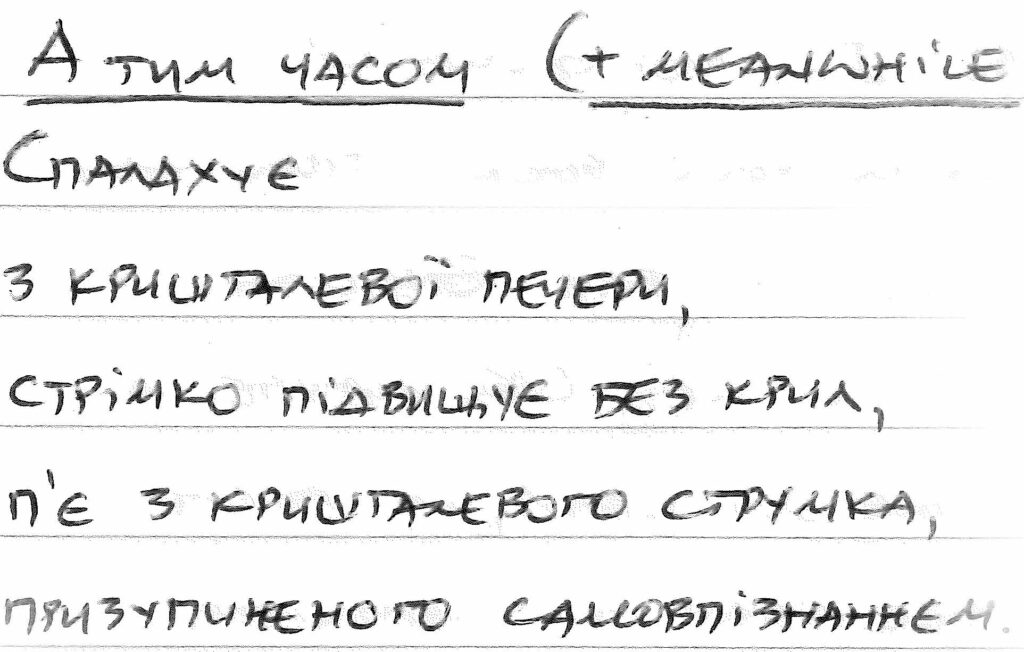

Andrei’s translation:

Meanwhile-translated-into-Ukr-by-Andrei-ENHANCED-3RD

The observer, hung wriggling

in another sticky web, configures

the observed accordingly.

That’s brilliant darling. The life you lead!!!

Gary, thank you for your insights here. On my iPad, Andrei’s translation is just a blank box.

I’ve had a lot of trouble posting this file, which is a scan of Andrei’s handwritten letter. But it may come up eventually, just very, very slowly. Unless you know Ukrainian, you aren’t going to be able to read it.

Hi Gary

OK. I am reading. Which is something I have not been interested in doing for quite a long while. So. You have got me reading which says a lot already about the magnetizing quality of how you write….and, OK…..what you write about. I am a deeply recovering post-modernist who swallowed the form pill and then fortified it with a swig of misunderstood Buddhism….thinking, you know, form is the thing, content is the passive passenger trying to get a word in, but the passenger could be talking about anything–the content doesn’t matter, it is empty you know, no true meaning there. But, somehow I am able to follow–and be actually interested in your content, the meanings of what you have to say–so, am I backsliding or is it a new dawn? Or, are you that good of a writer….? Anyway, thanks for writing and thank you for y’r full blown fidelity to words, to the word…… feels like you are all in on that.

Hmm. Is it form? Is it content? I once, within the poet Robert Creeley’s hearing, said to someone that I’d been focusing more on form in my writing at that time, whereas I had been more focused on content in the previous period. Vividly, I remember that he shook his head, and said, “It doesn’t work like that.” Well, geez, I thought, it seems like that’s what I’m doing, so how do you know? But then, ridiculously, I didn’t ask him to clarify, feeling intimidated. I’m sure he would have explained. I’ll guess that he didn’t see a difference between form and content.

I don’t know if that helps.

But, at any rate, I’ve been enjoying writing in this form (the blog), and it does seem like it’s focused on content, you know, not especially on making the writing beautiful or creative or something. It does come out in some kind of shape, which does require my standard sense of craft in wording, placement of information, etc, etc. What I think is that the form and content must be aligned well enough to engage you to read it, even if you’re not inclined, so something good is happening!

Gary

This is great – very articulate and excellent. My ex-Slovene husband, who has lived in the States for 20 years now, says he dreams, thinks, and curses in English -so it happens! Also, in SLO, they have nothing but English or German TV (except news and soap operas) – so basically, the Country is highly bi-lingual. Wonderful piece. M

I suppose it calls into question what a “native language” really is, and what really is the identity that goes with it?